This area contains periodic reflections by Douglas Worts on issues related to culture, museums and sustainability.

Reposted Feb 1, 2020

Originally posted March 1, 2020

When Museums Forget their Past…

…It is Hard to Move Forward

ICOM Canada publication on museums and

sustainability, for Summit of the

Museums of the Americas Conference, 1998, Costa Rica.

I recently came across a notice from ICOM Canada (International Council of Museums), inviting museum practitioners to contribute what their museum is doing to help address the unsustainability of current methods of travel and transport. It caused me to reflect on a time when I was on the ICOM Canada board of directors, specifically because we were engaged in many robust discussions about sustainability, culture and museums more than 20 years ago.

I was prompted to go searching for the ICOM Canada Bulletin which I organized and edited on this topic. Sadly, I found no sign of the publication or its component articles, neither on an ICOM website, nor anywhere on the internet. So, I went looking in my own archives and discovered the article I wrote that introduced this issue of Bulletin. It is gratifying that we were talking in substantive terms about the central issue of culture in our unsustainable world, and how museums could become catalysts for cultural change.

But it was discouraging that organizations, and even whole fields of endeavour, can so easily lose connection to their own past. And when that happens, forward movement is seriously curtailed.

Here is a glimpse into how ICOM Canada was talking about sustainability over two decades ago…

*********

Museums and Sustainability:

repositioning cultural organizations

Douglas Worts

March 2000

Sustainable Development — meeting the needs of today’s world without diminishing the capability of future generations to meet their needs.

… from “Our Common Future: the Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development (the Brundtland Report), UN, 1987.

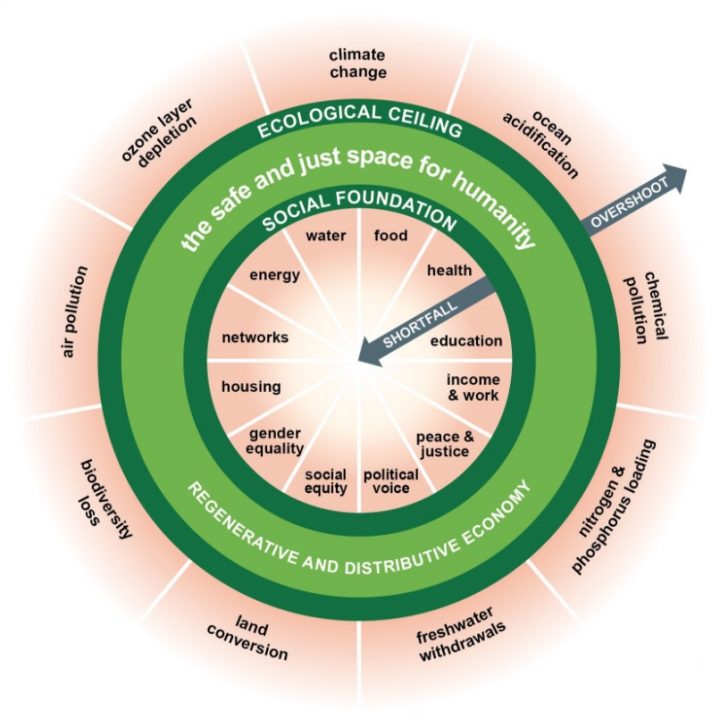

Sustainable Development (SD) provides a framework for re-thinking how humanity addresses the challenges of our times – including environmental health, social equity, humane urban planning and viable economic systems. We often think of ‘development’ as a process that pertains primarily to non-industrialized countries. Surely much technological and economic innovation is required if these countries are to play a partnership role in our increasingly globalized world. But industrialized countries have a lot of development to undergo as well. Problems of wealth distribution, racism and other systemic inequities, as well as environmental degradation and resource depletion, are evidence of cultural values in the West that are wholly unsustainable. (see Mathis Wackernagel and Bill Rees, Our Ecological Footprint, for a fascinating snapshot of our current reality).

As a holistic approach to development, ‘sustainability’ involves a balanced, integrated view of social, environmental and economic dimensions of our world. In order to ensure such a balanced approach to our collective future, several component pieces will be required. Innovative, technological solutions are needed for commodity production, recycling and waste management. New economic models must integrate into production systems an appreciation of both natural capital (ie. responsible use of natural resources) and social capital (ie. responsible approaches to how people affect and are affected by commercial initiatives). Improved social and environmental legislation, in both national and international arenas, is required to ensure that human and natural resources are treated with respect. Beyond these considerations, there must be acknowledgement that the foundation of a sustainable world will be found in human values and actions – both individually and collectively. Culture – which essentially reflects the ways we negotiate our conscious relationship with this world – is the domain in which sustainable values are either nurtured or starved. Family environments, schools, and vehicles of popular culture play central roles in the cultivation of our values – which to date have fallen well short of being sustainable. Since museums are, by nature, cultural organizations, they have the potential to play important roles in shaping our collective tomorrow.

There are many ways to live in the world, witnessed by the wide range of cultures that have enabled individuals to survive and flourish through past centuries. And although there are still countless cultures that cover the Earth, the forces of globalization are transforming all of them. As migration, technological communication and economic interconnectedness characterize our world in the year 2000, cultural systems that holistically embraced social, spiritual, environmental and economic dimensions of life are becoming splintered. And the western values that have lead us towards globalizing trends — specifically the desire for economic, intellectual and ideological power — are inserting themselves into other cultures. Finding ways to mediate the interactions of cultures, especially in pluralist communities, so that individuals live and participate consciously in ways that are sustainable, may constitute the toughest challenges that humanity has faced to date. One might ask, what does this have to do with museums?

In museums, we normally gauge our successes in terms of new acquisitions, the popularity of exhibitions, our comprehensive collections, scholarly publications, grants received and economic impacts – and I would suggest that we don’t measure these very convincingly. In some ways, museums are the perfect mirror for a culture dominated by hoarding values that encourage the acquisition of material wealth, power and influence – usually without much reflection on the broader implications of these activities. Yet museums have the capacity to transform themselves into much more effective ‘places of the muses’– where inspiration, creativity and insight is fostered across the population, and dialogue is facilitated between individuals and groups. In other words, museums can help facilitate two essential components of sustainability at the individual level – deep reflection on one’s place in the mystery of life, as well as participation in meaningful and respectful dialogue between people. To achieve this, however, many foundation-blocks of traditional museums will have to be rethought, including both values and practices.

In the spirit of embracing principles of sustainability, exciting initiatives within the museum community are well underway — from practical work on exhibits, to national policy reviews. This issue of ICOM Canada Bulletin is devoted to summarizing a range of exciting initiatives, each of which is attempting to explore different aspects of the question, ‘what is the potential of the museum to play a meaningful role in ensuring a sustainable future?’.

Renee Huard and Harm Sloterdjik, both from Montreal’s Biosphere, reflect on some of the early and more recent principles of sustainability, as embodied in their organization which was inspired by the vision of Buckminster Fuller. In a discussion of a new life sciences exhibition, Glenn Sutter, Curator at the Royal Saskatchewan Museum, introduces the complex issues associated with achieving sustainability. Robert Archibald, President of the Missouri Historical Society, provides a synopsis of an American Association of Museum’s national think-tank initiative that is attempting to articulate a plan for strengthening the relationship between museums and communities. David Dusome, Executive Director of Museums Alberta, introduces a national prototype project in Canada that will test new performance measurements for museums – such indicators will be critical in charting a new course for museums and assessing institututional successes. Nina Archabal, Director of the Minnesota Historical Society, writes about the role of culture and sustainability in an urban-renewal project in the American mid-west.

These are just some of the ways that museums around the world are re-evaluating how they can play the most valuable role in our turbulent and changing times. Some of the publications of ICOM and UNESCO provide particularly exciting visions for museums. Oddly enough, even organizations like the World Bank are slowly cluing into the central role that culture plays in any development initiative – and they have created some very valuable resources that are worth consulting.

Many in Canada are still unfamiliar with the Department of Canadian Heritage’s Strategy for Sustainable Development. Several years ago, the federal government passed legislation compelling over two dozen departments to develop SD strategies, and then update them every three years. In the Department of Canadian Heritage (DCH), the first strategy, implemented in 1997, was driven by Parks Canada and focusses primarily on parks-related, environmental issues. Now, on the cusp of its second strategy document, Parks Canada has become a separate agency – leaving the DCH to tackle the job of clarifying what role it sees for culture, arts and heritage in the quest for sustainability. Due out this autumn, the second SD Strategy for DCH will be worth watching for.

Increasingly, culture is finding itself at the centre of development initiatives around the world. Museums have an opportunity to play a meaningful role in mapping our collective future – but we will need to approach this prospect with humility and respect for scale of this undertaking.

*****

“Development divorced from its human or cultural context is growth without a soul.”

… from Our Creative Diversity: Report of the World Commission on Culture and Development, UNESCO, 1995

*****

Some useful references:

American Association of Museums, Excellence and Equity: Education and the Public Dimension of Museums. Washington, D.C.: American Association of Museums, 1992.

Amory Lovins, Hunter Lovins, Paul Hawkins, Natural Capitalism, Boston: Little, Brown and Co, 1999.

Goa, David, “Introduction”, in Cultural Diversity and Museums: Exploring Our Identities, Ottawa: Canadian Museums Association, 1994.

ICOM, “Museums and Cultural Diversity: Draft ICOM Policy Statement”, Report of the Working Group on Cross Cultural Issues, 1998.

Musee de la Civilisation, Museums and Sustainable Communities: A Canadian Perspective, Quebec City: ICOM Canada, 1998.

Rivard, Rene, “Ecomuseums in Quebec”, Museum, vol. 37/1985.

Ryan, William F, Culture, Spirituality and Economic Development, Ottawa: International Development Research Centre, 1995.

Tator, Carol, et al., Challenging Racism in the Arts: Case Studies of Controversy and Conflict, Toronto: U of T Press, 1998

UNESCO, “Action Plan on Cultural Policies for Development”, adopted in Stockholm, April 1998 by Intergovernmental Conference on Cultural Policies for Development.

UNESCO, Culture, Creativity and Markets – World Culture Report, Paris: UNESCO, 1998.

UNESCO, Our Creative Diversity: Report of the World Commission on Culture and Development, Paris: UNESCO, 1995.

Wackernagel, Mathis and William Rees. Our Ecological Footprint, Philadelphia, PA: New Society Publishers, 1996.

by Douglas Worts

July 2022

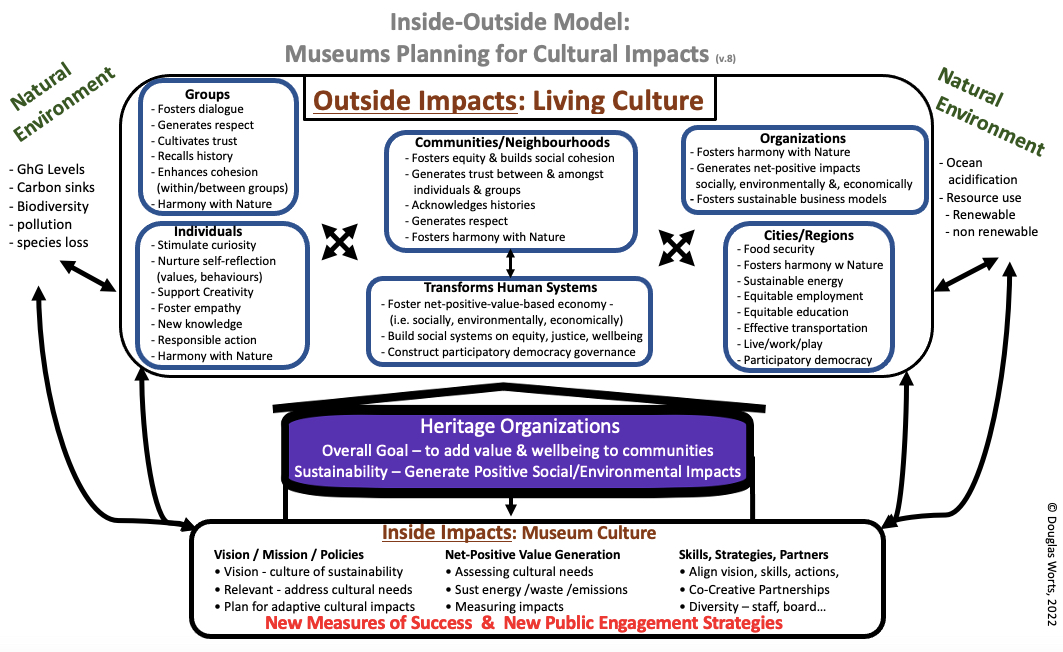

“The Inside-Outside Model: Museums Planning for Cultural Impacts”:

(A Planning Tool for Museums Striving to be Catalysts of Cultural Adaptation)

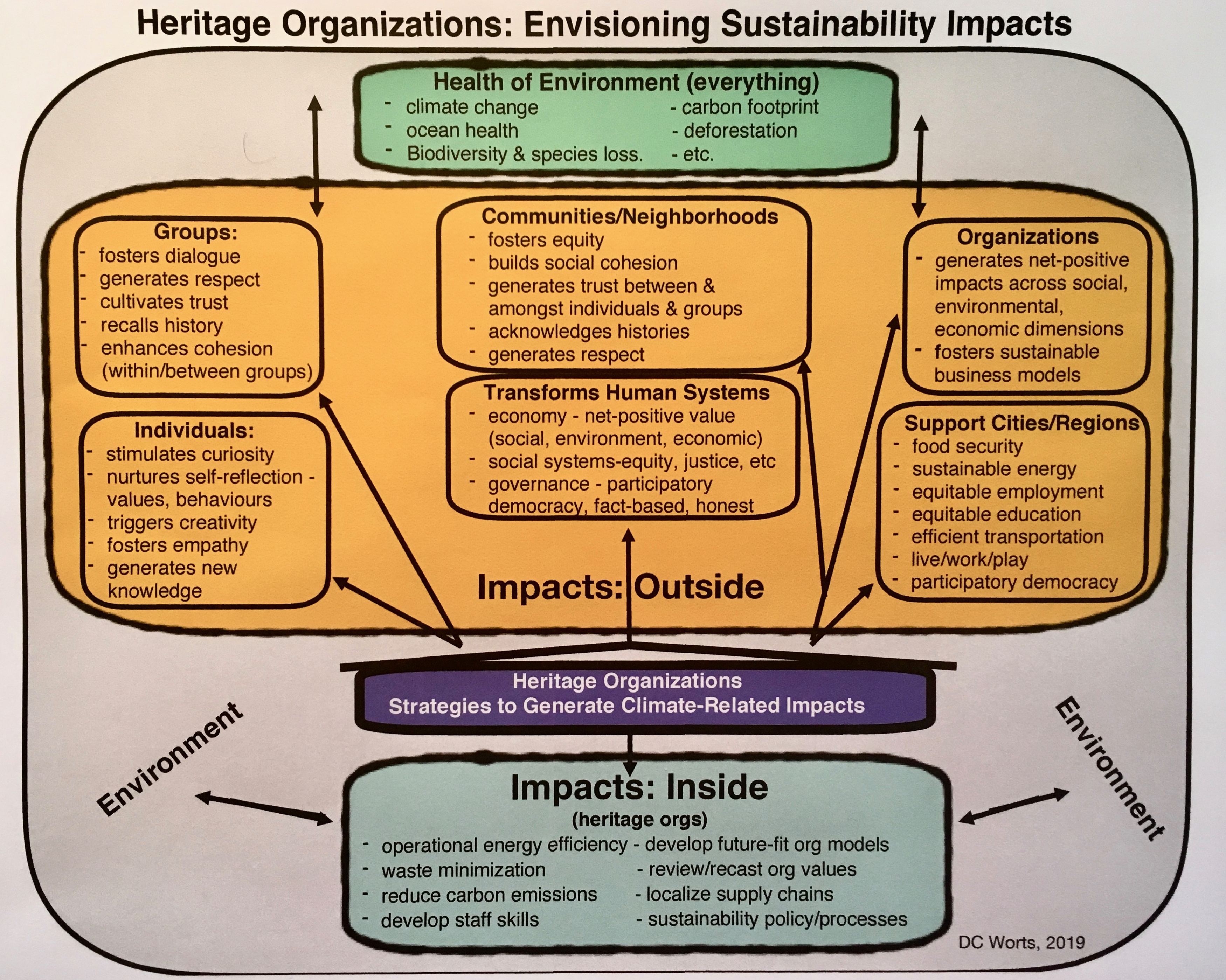

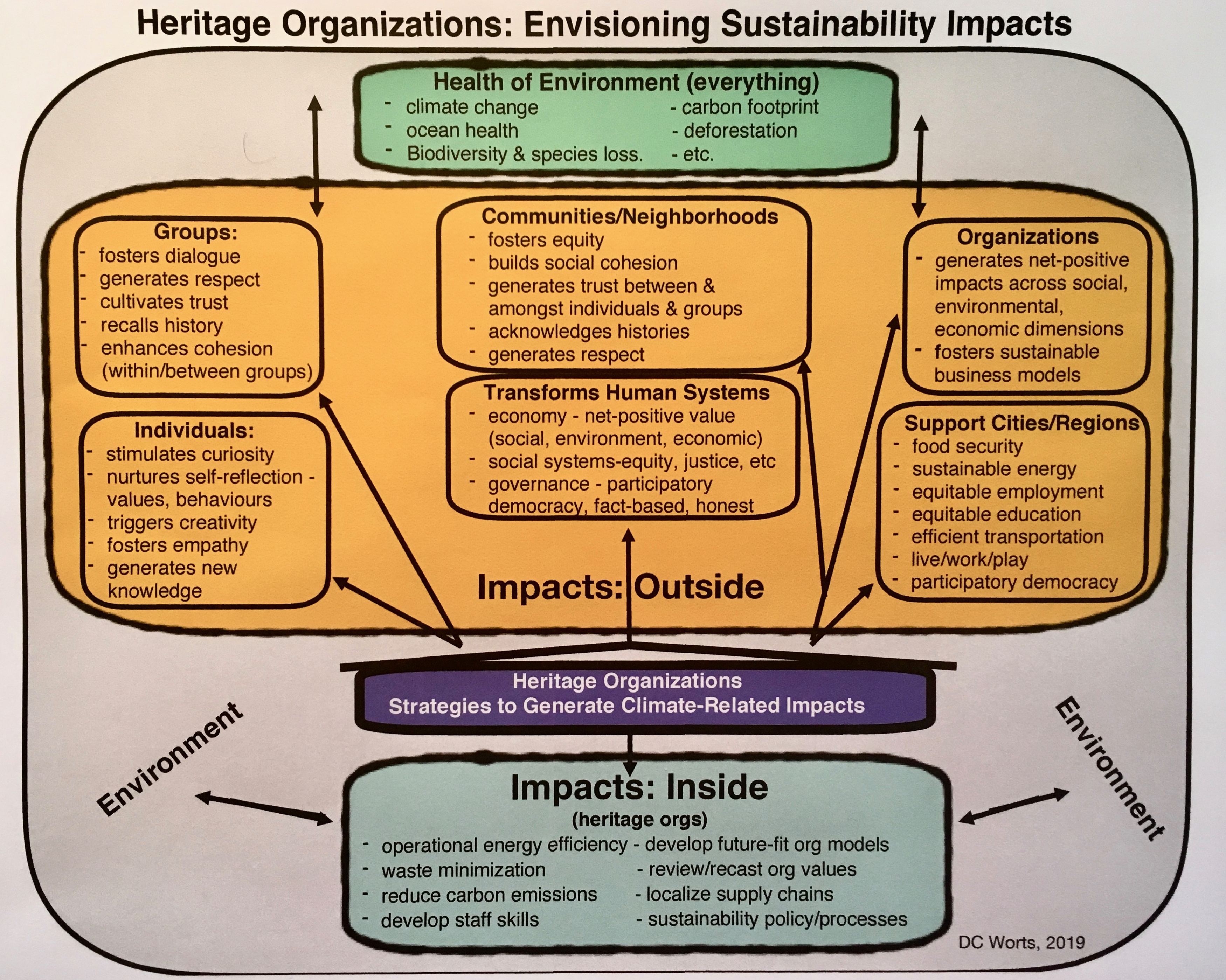

This article introduces a planning tool for museums that understand the big challenges of sustainability are rooted in the living culture. While it is true that operational efficiencies can reduce the harm done by traditional organizational practices, The greatest benefits for planet and people are to be found well beyond operational issues of the museum itself. The “Inside-Outside Model” can help museum staffs articulate assumptions about where and how cultural change can happen. Further, the model is designed to help museum professionals plan for their sustainability work to leverage ‘inside’ resources in order to generate meaningful ‘outside’ change across the many facets of culture, community and environment.

By Douglas Worts, Culture and Sustainability Specialist. (version 8 – updated July 23, 2022)

Humanity, and the Earth, have entered a new geologic period (formally known as an ‘epoch’), known as the Anthropocene. Starting in the mid-20th century, the #1 force affecting planetary systems became human beings. Simply put, the number of people living on Earth, combined with the extraordinary demands placed on Nature to provide everything we consume and then reprocess the colossal amount of human waste we produce, has overwhelmed the planet’s ability to regenerate itself. While it is important to remember that much good has been produced by human creativity in our world, the unintended consequences of ‘life as normal’ have slowly been eroding the planet’s ability to flourish. Sadly, humanity has been largely unconscious of the dangerous reality that comes from living life as we have evolved to do. Running down planetary systems may not have been a conscious choice of humanity, but there is a high price to pay.

Ironically, the brilliance of humanity’s technological and other advances, have come at the cost of threatening life as we know it on the planet. Arguably, this blend of achievement and destruction, has led to the growing divide between those who have power and those who do not. It is also interesting to observe the balance of conscious and unconscious implications of the behaviours associated with contemporary life. While most people understand that each individual is part of a sprawling human culture, distributed across a vast planet, each of us has some level of ignorance about the implications for other life forms of living the ways that we do. It is indeed a dangerous situation.

When populations were much smaller and largely focused within defined geographic regions, the activities of living cultures certainly had both creative and destructive sides. However, most of the positive and negative impacts were felt locally. In the 22nd century, current population levels, coupled with the interconnected nature of life, through economics, transportation, communication, business and more, has magnified the ‘footprint’ of humanity – if exceedingly unequally. Ironically, many earlier cultures were more aware of, and inclined to, acknowledge/appreciate the extraordinary power, mystery and magnificence of the Earth’s natural systems. Today, having a respectful relationship with Nature is not a requirement for people to consider themselves ‘successful’. Human pursuit of power and money lead many people to believe that they could dominate nature and place themselves above natural systems. Such pursuits have normalized trends that destroy the life-supporting environment on which we all depend.

So, today we see the long shadows of runaway climate change, species loss, ocean acidification, deforestation and other trends affecting Earth’s natural systems. Slowly, but increasingly, humanity is becoming convinced that human culture, (with its deep values, attitudes, traditions, behaviours, systems and processes) must change. However, there is no roadmap to guide humanity forward on this path. And because power is so unequally distributed within and across human societies, that it is easy to see how those with power do what they feel they must to hold onto their power. Those with less power naturally seek to acquire a fair share of influence. Such power imbalances often lead to conflict – thereby squandering time-limited opportunities. At this point, one might wonder if human culture is capable of mobilizing the humanistic values , as well as sufficient reflection, dialogue/cohesion and co-creative action, to steer our species towards safe harbour?

Humanity has unique abilities to cultivate values, principles, ethics, morality – all of which form vital parts of building strong relationships of trust and respect that can enable enormous wisdom, insight and creativity. The story of human evolution is well along the path to globalization on our planet. Science tells us that the biosphere has more than enough capacity to support all people and other species in lives that are rich and rewarding. But individuals and collectives who have strong commitments to amassing and holding onto power and influence, stand in the way of envisioning a way for all people to flourish on a healthy planet.

In recent years, museums and other cultural organizations have increasingly embraced the notion of ‘greening’. The idea is that our museums use a lot of energy and produce much waste and pollution – so it is important to increase their efficiency. However true this may be, (and it is true!), today’s existential crises, do not revolve around museum operations. Rather, the problems are rooted in the living cultures. What is needed is to shift the foundation blocks of the living culture(s) to align with a vision of flourishing and thriving. Yet, we have no clear vision of how 8 billion people can live on our planet in ways that support human happiness, wellbeing and continued adaptive change.

So…

- what would it take for museums to become catalysts of cultural adaptation and change?

- what would they have to do differently?

- what new skills must they acquire?

- how could they connect to the mainstream of living culture(s), in spite of their traditional model of operating almost entirely in the ‘leisure time economy’?

- What new partnerships could open up the ways in which all aspects of the living culture connect with museums (the mythic homes of the muses – capable of unleashing creativity, insight, wisdom, relatedness, compassion and more)?

- How do museums build on those aspects of past practices that have been successful at fostering public a) reflection; b) dialogue/cohesion-building; c) co-creative action?

The short answer to these questions, I believe, is… experimentation. It requires museums to think less about generating products for public consumption, and more about how can they engage the public in processes that surface the innate creativity and wisdom of the living culture to continuously adapt to a changing world.

Much could change if museums can develop new ways to work in partnership with individuals, groups, organizations, cities, nations and more. If the goal was to invite the creative ‘muses’ into forums for real-life, every-day decision-making environments, at a range of levels, then the processes of cultural adaptation will be alive, wherever they are needed.

It has always seemed to me to be an odd choice to place ‘culture’ into leisure time and tourism environments. Did someone expect that cultural insights would happen in leisure time, and then ‘trickle-down’ in some meaningful way? I understand that this can happen for the lucky individuals who might have this kind of experience in a museum. But the potential is great for museums to operate with intentionality, as they help bring together science, art, history, technology, engineering, philosophy, economics, governance and more, within the forums of real-life decision-making.

About four years ago I began developing a planning tool for museums. I wanted something that was simple in its basic concept, but which could contain a lot of complexity in terms of how museums could become catalysts of cultural adaptation. I could see that the challenge revolved around connecting what could be mobilized INSIDE the museum, in order to create meaningful change OUTSIDE the museum. The result was the “Inside-Outside Model: Museums Planning for Cultural Impacts”.

I have been developing this model for the past four years – but its roots go back decades in my work. The first version was published by the AASLH in April of 2019, as part of the work I was doing on the Sustainability Task Force for the organization.

There are a couple of new articles I am writing that focus on the Inside-Outside Model. I hope they will provide improvements to the model and to the supports that help people use it. I have presented the ideas in several conferences. One of these was the Ecomuseums and Climate conference that was a pre-event to COP 26. Held at the end of September 2021, I contributed a 12-minute presentation that provides a step by step introduction into how to understand and use the Model – available here: https://youtu.be/9iu3NFT1whs?t=103m20s

Let me know your thoughts about the “Inside-Outside Model: Museums Planning for Cultural Impacts”.

Douglas Worts, Culture & Sustainability Specialist, Toronto, Canada

March 2, 2021

Inside-Outside Model: Planning for Cultural Impacts

Here is a new tool I developed to help museum professionals consider the scope of options available for public engagement strategies that can impact the living culture in a host of ways. These range from:

- developing internally focused activities, like energy-efficient retrofits for their buildings,

- to outwardly focused impacts on individuals, groups, communities, cities, organizations, as well as

- to reimagining societal systems, like the economy, laws, and more.

I will return to this post shortly to expand the description of the Model.

download the file for 8.5″x11″ print – Inside-Outside Model – Summer 2021

July 18, 2020

Heritage Planning for Sustainable Cultural Impacts

NOTE: a shorter version was first published in 2019 on the AASLH Blog site (click here).

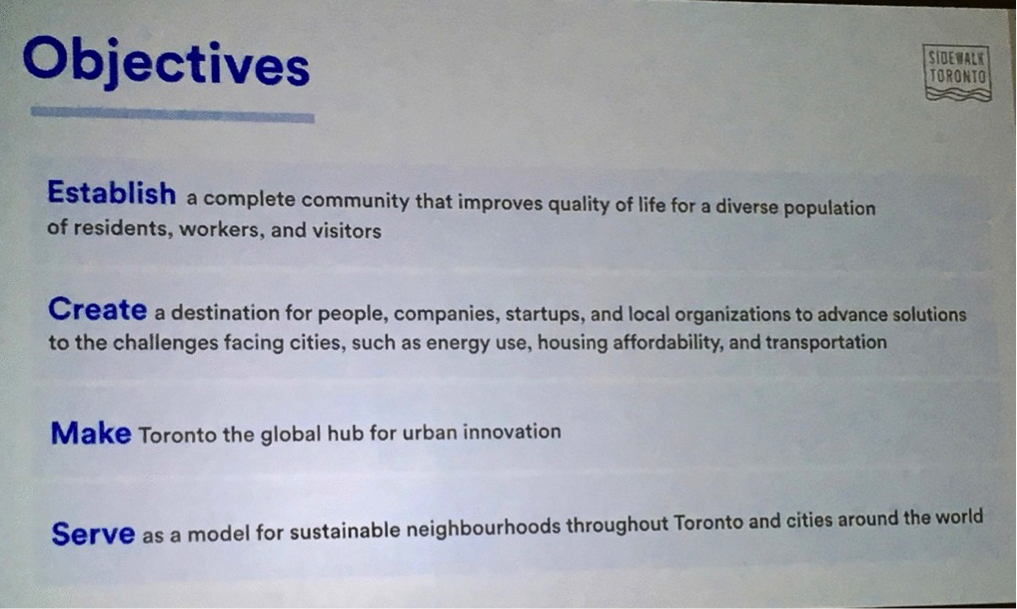

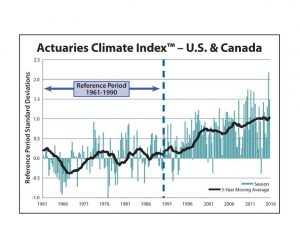

John Dichtl, the President and CEO of the American Association for State and Local History, wrote an inspiring post in early 2019, about climate change and its implications for the heritage sector. It was published on the AASLH blog site (click HERE). In his post, Dichtl paints a big picture related to the phenomenon of climate change, asserting a cause/effect relationship between human culture and our transforming climate. John invokes insights coming from history, science and social science – three central pillars of human knowledge creation – as being capable to helping to guide humanity forward through the treacherous waters we find ourselves in the early 21st century.

In his call to action, John suggests that the heritage sector can and should embrace climate change as a focus for our public engagement efforts. Similar to how our sector has focused on the vital topics of equity, diversity and justice in our society, climate change belongs on that list of essential issues of our time. His assertion that history and related disciplines provide a solid, evidence-based foundation that is driven by a pursuit of truth, is a strong argument for enhancing the roles of heritage organizations in grappling with the forces that are shaping contemporary culture. Certainly current trends in using false statements to manipulate citizens and governments are worrying. Not only are false statements dishonest, but they are divisive and promote violence. Humanity has more than enough to deal with at this point in time, without the chaos produced by normalizing fictional facts. If humanity has a chance of achieving a sustainable future, we must build and maintain a solid foundation of values and behaviours that are guided by a common understanding of the difference between truth and falseness.

John makes many good points about the heritage field needing to embrace the challenges of dealing with climate change. Certainly extreme weather events do threaten to damage the physical fabric of museums and other cultural facilities. Protecting existing properties, collections, archives and other assets is important. Such activities however, need to be seen within the larger context of the leadership role that our sector can play as catalysts of cultural change and adaptation across society. The essential processes needed to manage the complexity and scope of current challenges and opportunities involve the effective use of ‘systems thinking’.

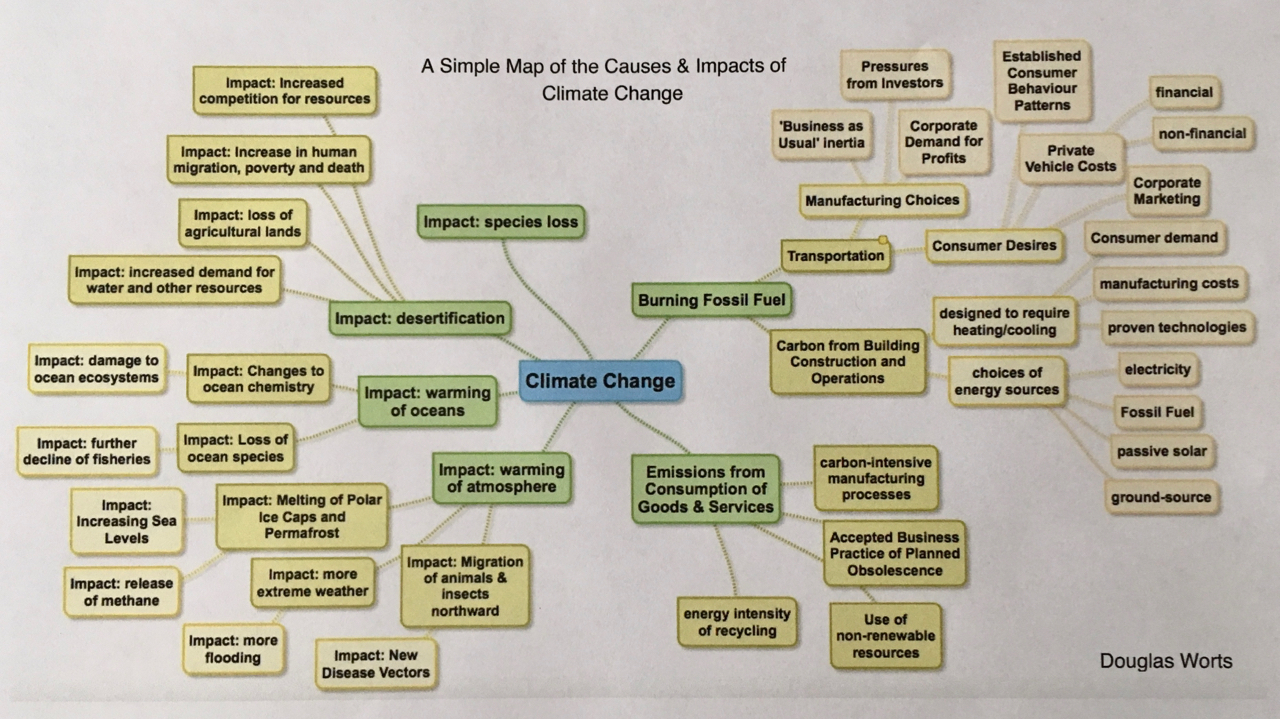

Climate destabilization, like racism, inequality and injustice, are all symptoms of bigger and deeper problems. The situation is not unlike going to a doctor because you have trouble breathing. After some tests, and a confirmation that pneumonia is present, it is relatively straight-forward to treat the illness. However, it is vital to determine whether the lung disease is a primary or secondary condition. If there is an underlying cancer that caused the pneumonia, it is vital that all efforts are taken to treat the cancer, at the same time that the pneumonia is being treated. When mapping the causes of a changing climate, it is clear that climatic changes are driven to a large extent by greenhouse gases (GhGs). Most people have learned that GhGs come from many sources, but mostly the burning of petroleum products. And it is human demand for energy and the corporate need for wealth generation that are the drivers of current fossil fuel use. Our society seems determined to retain its reliance on unfathomable amounts of energy required to power its transportation, housing, manufacturing, and so much more. So what can heritage organizations do?

If museums and other cultural organizations were able to leverage insights from how humans in the past have navigated crises, they then could be applied in ways that help the living culture to adapt to our changing world. We could help manifest the old saying ‘we stand on the shoulders of ancestors’ – not simply duplicating or continuing what has come before, but rather to use our insights into the past as a way to better inform how societies assess current changes in the world and proactively adapt. Playing such a role would require considerable innovation within the cultural field, as well as working with partners in new ways. Such a change within the heritage field could feel uncomfortable, especially for those who see cultural and heritage organizations playing fixed roles that were developed in the past. It is virtually certain that there would be need to share authority with vision/values-aligned partners, become increasingly co-creative and develop the ability to measure ‘success’ in the impacts created in the larger world (going well beyond simple visitation and revenue stats).

As humanity grapples with the prospect of widespread climate destabilization, humans have a few options:

- dramatically reduce consuming energy as we do;

- find a substitute approach to providing energy, specifically renewable energy; or

- continue business as usual and make the world uninhabitable for humans.

If existing energy corporations embraced the option of transforming the global energy system (e.g. through a transition to renewables), then a huge amount of time could be secured to rethink how humanity can live successfully on this planet. Since oil companies and their investors, as well as governments and many customers do not seem prepared to exercise this leadership option, a serious crisis simply gets worse. It is like ignoring an underlying cancer. Who would have thought that so many people in our world would be so resistant to recognizing a crisis, especially with all the scientific evidence being clear about how human cultures are driving climate change in perilous ways? Bridging this gap between reality and understanding/belief is fundamentally a cultural challenge. Not the kind of challenge that cultural organizations are used to – but increasingly the ones that require being addressed.

The heritage sector has the ability to foster conscious cultural change as demonstrated by its many amazing attributes, including, how this sector:

- extends across the country and around the world

- operates in virtually in every community

- enjoys close links to the general public

- maintains a very high level of public trust

- is solidly rooted in many disciplines that are based on rational, evidence-based knowledge and continuous improvement through research

- are the custodians of a large quantity of culturally significant tangible and intangible heritage, all of which is invaluable for catalyzing and guiding our constantly-evolving culture.

In John’s post, he has emphasized the value of the heritage sector getting ahead of climate and weather trends that threaten to cause irreparable harm to individual sites and collections. This makes good sense from the vantage point of an organization that believes that safeguarding its physical manifestation is its principal concern. But it worth recognizing that securing sites and collections falls well short of catalyzing meaningful, adaptive change within the living culture, not only the corporate culture.

The complexity of altering existing climate trends that are driven by producers retailers, investors, consumers, governments, legal systems, etc. that make up our culture, suggest that we need to create a systems-thinking framework to deal with this ‘wicked problem’. This is not only true for climate change problems, but also for the myriad forms of inequity, violence, abuse and more that have become baked into the systems that shape how our cultures and our societies.

If heritage and cultural organizations are seen as having the potential to become catalysts of cultural adaptation, then it is best to have a map of how to aim for two general types of positive impacts/outcomes. As John has suggested, one refers to ‘inner’ transformations and impacts that affect the internal culture of organizations. The second refers to organizational strategies that lead to ‘outer’ transformations and impacts across the living culture.

My goal in creating the model below was to offer a planning approach for heritage organizations to:

- identify ways that will make existing organizational resources as resilient and effective as possible (INSIDE), and

- offer a framework for how individual organizations, in concert with a wide spectrum of potential values-aligned partner organizations (including progressive businesses, foundations, governments and so on), can become catalysts of co-creative public engagement & cultural change (OUTSIDE).

At the centre of this model are the Heritage Organizations, which generate operational and public engagement strategies, designed to have meaningful impacts. When it comes to a goal like addressing the climate crisis, one group of these strategies may be designed to generate INSIDE IMPACTS – for example efforts that improve energy efficiency, or reduce waste, such as CO2 emissions. Inner strategies also include the potential acquisition of new skillsets to develop capacity for generating new kinds of strategies beyond the organization, such as skills in conducting cultural needs analyses, forging effective partnerships or carrying out public impact studies. The second group of strategies include many a broad range of OUTSIDE IMPACTS, across the living culture. These are inherently more difficult to achieve, because they are, by their nature, beyond the control of the cultural organization. Nonetheless, if there is need for cultural adaptation across individuals, communities, organizations, cities, and social/economic systems, then doesn’t it make sense that cultural organizations are primary players as catalysts in this kind of change?

Museums do have some history of generating impacts within the living culture, however, most of this is limited to impacts involving a sub-set of individuals and groups who visit a museum or heritage facility during their leisure time. In the Inside/Outside Model I have offered up here, the scope of potential impact areas that are perhaps less familiar to most museum professionals. Specifically I’ve suggested that museums and cultural organizations plan for impacts at the levels of groups, neighbourhoods, communities, other organizations (both for-profits and non-profits), cities, as well as social/economic systems and human/environmental relationships. Each of these focuses will have different challenges and opportunities that will need to be named clearly, strategies developed to catalyze the impacts and ultimately to assess outcomes. Much experimentation and testing will be required for the field to fully move into these areas of engaging the population in co-creative processes that catalyze meaningful cultural change.

One of the notable aspects of the INSIDE/OUTSIDE Model is that the heritage sector, along with all of humanity, is contained within the natural environment. So, whatever is done by any part of human society, has direct impacts on Nature (intentionally or unintentionally) – all of which needs to be understood and incorporated into the planning of public engagement strategies. This is particularly true because human systems and cultures currently generate a wide array of unintended consequences that must be reined in as they are made more conscious. The climate crisis, as well as pervasive systemic racism, are examples of unintended, or at least unowned consequences of the cultural status quo – and only cultural change can transform such damage into new cultural norms that enable humanity to continue into the future..

Another, very traditional ‘museum’ tradition that begs to be addressed adequately involves tourism. Any organization that depends heavily on tourism for attendance and revenue generates a massive carbon footprint, simply by its relationship to how tourists travel, what they consume and how they contribute to a given community. Currently, the calculations of tourism spending are extremely problematic because these have large carbon footprints that contribute to the destruction of the biosphere, and which are largely unaccounted for and completely unowned by any of the stakeholders.

A museum sector that set its priorities on addressing the cultural issues of the local living culture, and then approaches tourism as a secondary focus, might be a much more workable model. In this scenario, tourist experiences would revolve less around sites, objects and histories and more around building tourist knowledge and appreciation of how the local culture operates as it leverages its heritage(s), arts and creativity to generate effective cultural change and adaptation. In our pluralistic and globalized world, it seems vital that people can connect to lived realities in other parts of the world. This would help to build greater relationship, empathy, and cohesion. It is important to remember that, until we can eliminate greenhouse gas emissions from our energy and consumption, travel will be a threatening problem from a climate perspective. However, alternatives already exist and can be scaled, if only humanity could put an end to a 19th century approach to energy, consumption, and economics.

The museum sector derives great strength from the complex relationships it has with individuals, groups, organizations, communities and systems. Extending beyond the traditional notion of museums as providers of ‘service’, cultural organizations that embrace a vision of museums as cultural catalysts will require that we and our colleagues both understand and grapple with the challenges and opportunities for working collaboratively with partners to achieve meaningful cultural impacts.

The INSIDE/OUTSIDE Model is only a piece of the puzzle of how best to foster a culture of sustainability and flourishing. Nonetheless, I hope that this model generates discussion and creativity on the question of ‘how can heritage organizations help facilitate adaptive cultural change, in our fast-changing world’?

***

Douglas Worts is a ‘culture and sustainability specialist’, living in Toronto, Canada. He has been a museum professional for over 40 years, focused variously on interpretive planning, audience research, education technologies and teaching museology. Since 1997, his main interest has been in the cultural dimensions of humanity’s unsustainability, and the potential role of museums to foster cultural and adaptive change.

website: WorldViewsConsulting.ca

by Douglas Worts

March 1, 2020

When Museums Forget their Past… …It is Hard to Move Forward

I recently came across a notice from ICOM Canada (International Council of Museums), inviting museum practitioners to contribute what their museum is doing to help address the unsustainability of current methods of travel and transport. It caused me to reflect on a time when I was on the ICOM Canada board of directors, specifically because we were engaged in many robust discussions about sustainability, culture and museums more than 20 years ago.

I was prompted to go searching for the ICOM Canada Bulletin which I organized and edited on this topic. Sadly, I found no sign of the publication or its component articles, neither on an ICOM website, nor anywhere on the internet. So, I went looking in my own archives and discovered the article I wrote that introduced this issue of Bulletin. It is gratifying that we were talking in substantive terms about the central issue of culture in our unsustainable world, and how museums could become catalysts for cultural change.

But it was discouraging that organizations, and even whole fields of endeavour, can so easily lose connection to their own past. And when that happens, forward movement is seriously curtailed.

Here is a glimpse into how ICOM Canada was talking about sustainability over two decades ago…

*********

Museums and Sustainability:

repositioning cultural organizations

Douglas Worts

March 2000

Sustainable Development — meeting the needs of today’s world without diminishing the capability of future generations to meet their needs.

… from “Our Common Future: the Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development (the Brundtland Report), UN, 1987.

Sustainable Development (SD) provides a framework for re-thinking how humanity addresses the challenges of our times – including environmental health, social equity, humane urban planning and viable economic systems. We often think of ‘development’ as a process that pertains primarily to non-industrialized countries. Surely much technological and economic innovation is required if these countries are to play a partnership role in our increasingly globalized world. But industrialized countries have a lot of development to undergo as well. Problems of wealth distribution, racism and other systemic inequities, as well as environmental degradation and resource depletion, are evidence of cultural values in the West that are wholly unsustainable. (see Mathis Wackernagel and Bill Rees, Our Ecological Footprint, for a fascinating snapshot of our current reality).

As a holistic approach to development, ‘sustainability’ involves a balanced, integrated view of social, environmental and economic dimensions of our world. In order to ensure such a balanced approach to our collective future, several component pieces will be required. Innovative, technological solutions are needed for commodity production, recycling and waste management. New economic models must integrate into production systems an appreciation of both natural capital (ie. responsible use of natural resources) and social capital (ie. responsible approaches to how people affect and are affected by commercial initiatives). Improved social and environmental legislation, in both national and international arenas, is required to ensure that human and natural resources are treated with respect. Beyond these considerations, there must be acknowledgement that the foundation of a sustainable world will be found in human values and actions – both individually and collectively. Culture – which essentially reflects the ways we negotiate our conscious relationship with this world – is the domain in which sustainable values are either nurtured or starved. Family environments, schools, and vehicles of popular culture play central roles in the cultivation of our values – which to date have fallen well short of being sustainable. Since museums are, by nature, cultural organizations, they have the potential to play important roles in shaping our collective tomorrow.

There are many ways to live in the world, witnessed by the wide range of cultures that have enabled individuals to survive and flourish through past centuries. And although there are still countless cultures that cover the Earth, the forces of globalization are transforming all of them. As migration, technological communication and economic interconnectedness characterize our world in the year 2000, cultural systems that holistically embraced social, spiritual, environmental and economic dimensions of life are becoming splintered. And the western values that have lead us towards globalizing trends — specifically the desire for economic, intellectual and ideological power — are inserting themselves into other cultures. Finding ways to mediate the interactions of cultures, especially in pluralist communities, so that individuals live and participate consciously in ways that are sustainable, may constitute the toughest challenges that humanity has faced to date. One might ask, what does this have to do with museums?

In museums, we normally gauge our successes in terms of new acquisitions, the popularity of exhibitions, our comprehensive collections, scholarly publications, grants received and economic impacts – and I would suggest that we don’t measure these very convincingly. In some ways, museums are the perfect mirror for a culture dominated by hoarding values that encourage the acquisition of material wealth, power and influence – usually without much reflection on the broader implications of these activities. Yet museums have the capacity to transform themselves into much more effective ‘places of the muses’– where inspiration, creativity and insight is fostered across the population, and dialogue is facilitated between individuals and groups. In other words, museums can help facilitate two essential components of sustainability at the individual level – deep reflection on one’s place in the mystery of life, as well as participation in meaningful and respectful dialogue between people. To achieve this, however, many foundation-blocks of traditional museums will have to be rethought, including both values and practices.

In the spirit of embracing principles of sustainability, exciting initiatives within the museum community are well underway — from practical work on exhibits, to national policy reviews. This issue of ICOM Canada Bulletin is devoted to summarizing a range of exciting initiatives, each of which is attempting to explore different aspects of the question, ‘what is the potential of the museum to play a meaningful role in ensuring a sustainable future?’.

Renee Huard and Harm Sloterdjik, both from Montreal’s Biosphere, reflect on some of the early and more recent principles of sustainability, as embodied in their organization which was inspired by the vision of Buckminster Fuller. In a discussion of a new life sciences exhibition, Glenn Sutter, Curator at the Royal Saskatchewan Museum, introduces the complex issues associated with achieving sustainability. Robert Archibald, President of the Missouri Historical Society, provides a synopsis of an American Association of Museum’s national think-tank initiative that is attempting to articulate a plan for strengthening the relationship between museums and communities. David Dusome, Executive Director of Museums Alberta, introduces a national prototype project in Canada that will test new performance measurements for museums – such indicators will be critical in charting a new course for museums and assessing institututional successes. Nina Archabal, Director of the Minnesota Historical Society, writes about the role of culture and sustainability in an urban-renewal project in the American mid-west.

These are just some of the ways that museums around the world are re-evaluating how they can play the most valuable role in our turbulent and changing times. Some of the publications of ICOM and UNESCO provide particularly exciting visions for museums. Oddly enough, even organizations like the World Bank are slowly cluing into the central role that culture plays in any development initiative – and they have created some very valuable resources that are worth consulting.

Many in Canada are still unfamiliar with the Department of Canadian Heritage’s Strategy for Sustainable Development. Several years ago, the federal government passed legislation compelling over two dozen departments to develop SD strategies, and then update them every three years. In the Department of Canadian Heritage (DCH), the first strategy, implemented in 1997, was driven by Parks Canada and focusses primarily on parks-related, environmental issues. Now, on the cusp of its second strategy document, Parks Canada has become a separate agency – leaving the DCH to tackle the job of clarifying what role it sees for culture, arts and heritage in the quest for sustainability. Due out this autumn, the second SD Strategy for DCH will be worth watching for.

Increasingly, culture is finding itself at the centre of development initiatives around the world. Museums have an opportunity to play a meaningful role in mapping our collective future – but we will need to approach this prospect with humility and respect for scale of this undertaking.

*****

“Development divorced from its human or cultural context is growth without a soul.”

… from Our Creative Diversity: Report of the World Commission on Culture and Development, UNESCO, 1995

*****

Some useful references:

American Association of Museums, Excellence and Equity: Education and the Public Dimension of Museums. Washington, D.C.: American Association of Museums, 1992.

Amory Lovins, Hunter Lovins, Paul Hawkins, Natural Capitalism, Boston: Little, Brown and Co, 1999.

Goa, David, “Introduction”, in Cultural Diversity and Museums: Exploring Our Identities, Ottawa: Canadian Museums Association, 1994.

ICOM, “Museums and Cultural Diversity: Draft ICOM Policy Statement”, Report of the Working Group on Cross Cultural Issues, 1998.

Musee de la Civilisation, Museums and Sustainable Communities: A Canadian Perspective, Quebec City: ICOM Canada, 1998.

Rivard, Rene, “Ecomuseums in Quebec”, Museum, vol. 37/1985.

Ryan, William F, Culture, Spirituality and Economic Development, Ottawa: International Development Research Centre, 1995.

Tator, Carol, et al., Challenging Racism in the Arts: Case Studies of Controversy and Conflict, Toronto: U of T Press, 1998

UNESCO, “Action Plan on Cultural Policies for Development”, adopted in Stockholm, April 1998 by Intergovernmental Conference on Cultural Policies for Development.

UNESCO, Culture, Creativity and Markets – World Culture Report, Paris: UNESCO, 1998.

UNESCO, Our Creative Diversity: Report of the World Commission on Culture and Development, Paris: UNESCO, 1995.

Wackernagel, Mathis and William Rees. Our Ecological Footprint, Philadelphia, PA: New Society Publishers, 1996.

by Douglas Worts

January 10, 2020

Measuring Carbon – a Complex Challenge

October 26, 2019

October 18, 2019

Climate Change, Flying and Guilt: the Need to Change Culture as we Modify Behaviours

“JUST 12 PERCENT OF AMERICANS TAKE TWO-THIRDS OF ALL FLIGHTS” (AND I SUSPECT THAT THIS IS LIKELY TRUE FOR PEOPLE IN OTHER WESTERN COUNTRIES AS WELL”.

August 26, 2019

Checking in on Climate Science, its Trends and Tipping Points: Plus… a Couple of Tools for Museums to Help Plan for Climate Change Programming & Projects

- it clarifies the climate science within the framework of Earth’s complex system

- it illustrates how exponential growth in population, cities, consumption, energy use and pollution are affecting the planetary system

- it sketches what can be expected from our changing climate, and when, using scientific, data-driven modelling techniques

- it underscores the need for urgency in humanity becoming net-zero in terms of carbon emissions.

July 29, 2019

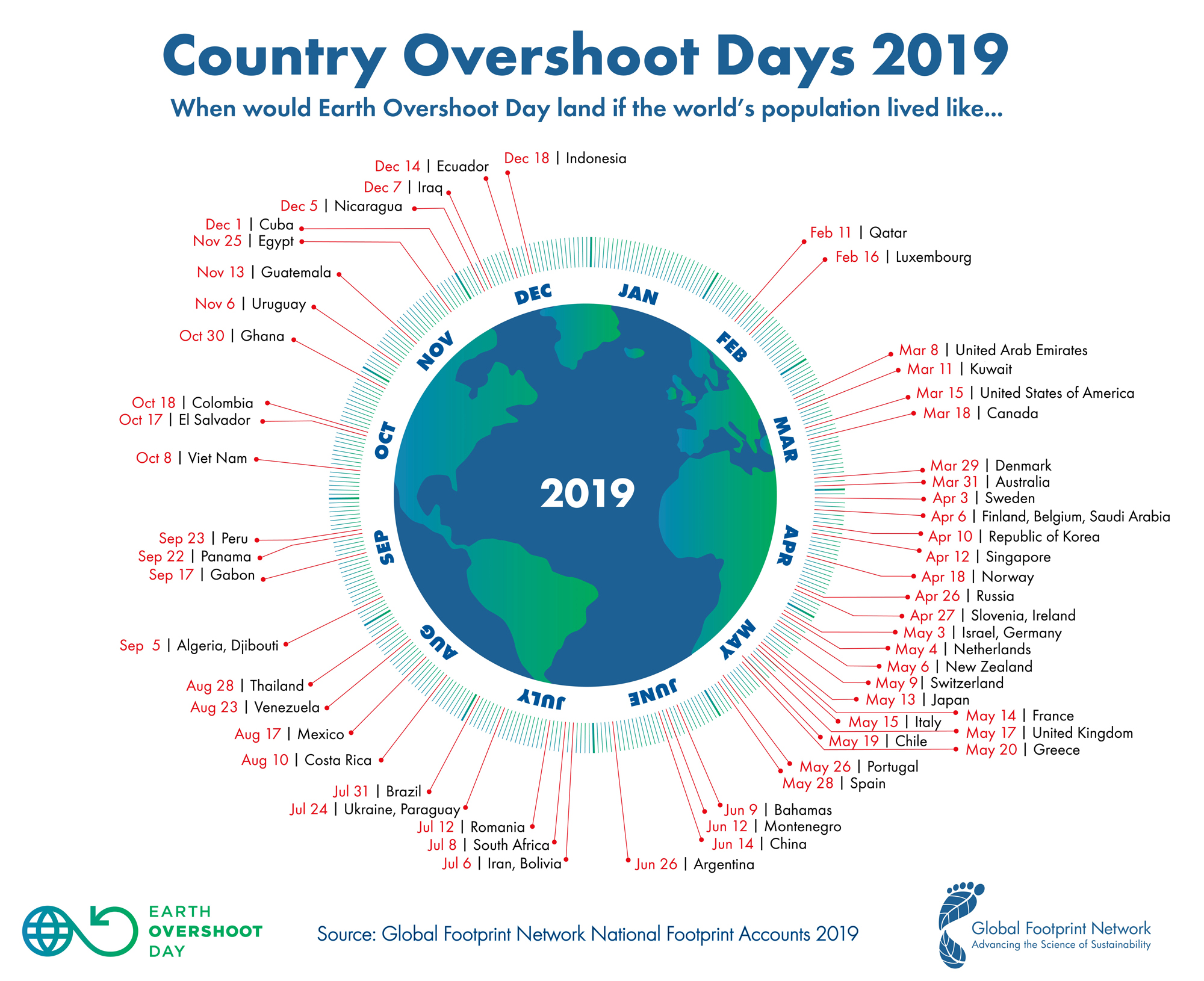

Global Overshoot Day, 2019 – Opportunities for Museums and Cultural Adaptation

April 29, 2019

Heritage Planning for Sustainable Cultural Impacts

NOTE: a shortened version of this article was first published on the Blog site of the American Association for State and Local History (AASLH) – (click here). I have been a member of the AASLH Sustainability Task force since early 2018.

AASLH President & CEO, John Dichtl, has written an inspiring post in his column for History News, and reproduced on the AASLH blog site (CLICK HERE) – one that is appropriate to this moment in time for our culture. He paints a big picture related to the phenomenon of climate change, asserting a cause/effect relationship between human culture and our transforming climate. John invokes insights coming from history, science and social science – three pillars of human knowledge creation – as being capable to helping to guide humanity through treacherous waters into the future.

In his call to action, John suggests that the heritage sector can and should embrace climate change as a focus for our public engagement efforts. Similar to how our sector has focused on the vital topics of equity, diversity and justice in our society, climate change belongs on that list of essential issues of our time. His assertion that history and related disciplines provide a solid, evidence-based foundation that is driven by a pursuit of truth, is a strong argument for enhancing the roles of heritage organizations in grappling with the forces that are shaping contemporary culture. Certainly current trends in using false statements to manipulate citizens and governments are worrying. Not only are false statements dishonest, but they are divisive and promote violence. Humanity has more than enough to deal with at this point in time, without the chaos produced by normalizing fictional facts. If humanity has a chance of achieving a sustainable future, we must build and maintain a solid foundation of values and behaviours that are guided by a common understanding of the difference between truth and falseness.

John makes many good points about the heritage field needing to embrace the challenges of dealing with climate change. Certainly extreme weather events do threaten to damage the physical fabric of museums and other cultural facilities. Protecting existing properties, collections, archives and other assets is important. Such activities however, need to be seen within the larger context of the leadership role that our sector can play as catalysts of cultural change and adaptation across society. The critical process needed to manage the complexity and scope of current challenges and opportunities is the effective use of ‘systems thinking’.

Climate destabilization, like racism, inequality and injustice, are all symptoms of bigger and deeper problems. The situation is not unlike going to a doctor because you have trouble breathing. After some tests, and a confirmation that pneumonia is present, it is relatively straight-forward to treat the illness. However, It is vital to determine whether the lung disease is a primary or secondary condition. If there is an underlying cancer that caused the pneumonia, it is essential that all efforts are taken to treat the cancer, at the same time that the pneumonia is being treated. When mapping the causes of a changing climate, it is clear that climatic changes are driven to a large extent by greenhouse gases (GhGs). Most people have learned that GhGs come from many sources, but mostly the burning of petroleum products. And it is human demand for energy and the corporate need for wealth generation that are the drivers of fossil fuel use. Our society seems determined to retain its reliance on unfathomable amounts of energy required to power transportation, housing, manufacturing, and so much more. So what can heritage organizations do? If they were able to leverage insights from how humans in the past have navigated crises in the past, then the old saying ‘we stand on the shoulders of ancestors’ could be applied in ways that help the living culture to adapt to our changing world. Such a scenario would require considerable innovation within the cultural field, and it would feel uncomfortable. It would be similar to the doctor who, while treating a lung disease, discovered an underlying cancer, would need to call in other specialists.

As humanity grapples with the prospect of widespread climate destabilization, humans have a few options:

- dramatically reduce consuming energy as we do;

- find a substitute approach providing energy, specifically renewable energy; or

- continue business as usual and make the world uninhabitable for humans.

If existing energy corporations embraced the option of transforming the global energy system (e.g. through a transition to renewables), then a huge amount of time could be secured to rethink how humanity can live successfully on this planet. Since oil companies and their investors, as well as governments and many customers do not seem prepared to exercise this leadership option, a crisis simply gets more serious. It is like ignoring an underlying cancer. Who would have thought that so many people in our world would be so resistant to recognizing a crisis, especially with all the scientific evidence being clear? Bridging this gap between reality and understanding/belief is fundamentally a cultural challenge. Not the kind cultural organizations are used to – but increasingly the ones that require being addressed.

The heritage sector has the ability to foster conscious cultural change as demonstrated by its many amazing attributes, including the heritage and cultural sector:

- extends across the country and around the world

- operates in virtually in every community

- enjoys close links to the general public

- maintains a very high level of public trust

- is solidly rooted in many disciplines that are based on rational, evidence-based knowledge and continuous improvement through research

- are the custodians of a large quantity of culturally significant tangible and intangible heritage, all of which is invaluable for catalyzing and guiding our constantly-evolving culture.

In John’s post, he has emphasized the value of the heritage sector getting ahead of climate and weather trends that threaten to cause irreparable harm to individual sites and collections. This makes good sense. And, since climate change can be seen as an advanced case of pneumonia, which is a secondary condition to the primary problem of an underlying ‘cancer’, it is important to be using a systems thinking framework to deal with the complexity of this large, ‘wicked problem’.

If heritage and cultural organizations are seen as having potential as catalysts of cultural adaptation, then it is best to have a map of how to aim for two general types of positive impacts. As John has suggested, one refers to ‘inner’ transformations and impacts, while the other refers to public strategies that lead to ‘outer’ transformations and impacts. My goal with the model below is to offer a planning approach for heritage organizations to:

- identify ways that will make existing resources as resilient as possible (INSIDE), and

- offer a framework for how individual sites, in concert with a wide spectrum of potential values-aligned partner organizations (including progressive businesses, foundations, governments and so on), can become catalysts of public engagement and cultural change (OUTSIDE).

At the heart of this model are the Heritage Organizations, which generate strategies, designed to have meaningful impacts. One group of these strategies may be designed to generate INSIDE IMPACTS – for example ones that improve energy efficiency, or reduce waste, such as CO2. Inner strategies also include acquiring new skill sets to develop capacity for working towards new kinds of outside strategies, such as conducting cultural needs analyses or impact studies. The second group of strategies are designed to generate OUTSIDE IMPACTS. This includes some traditional activities, such as programs to engage and impact individuals, families and groups. For many, new opportunities are suggested for impacts at the levels of communities, neighbourhoods, other organizations (both for-profits and non-profits) as well as cities. Each of these focuses will have different challenges and opportunities that will need to be assessed. Much experimentation and testing will be required for the field to fully move into these areas of catalyzing cultural change.

One of the notable aspects of this model is that the heritage sector, along with all of humanity, is contained within the natural environment. So whatever is done, by any part of human society, has direct impacts on Nature – all of which need to be understood and incorporated into the strategies. One example is that any organization that relies heavily on tourism for attendance, generates a large carbon footprint simply by its relationship to tourists and how they travel. Our sector has complex relationships, which provide challenges, but also great opportunities for cultural impacts. I hope that this model generates discussion and creativity on the question of ‘how can heritage organizations help facilitate adaptive cultural change, in a fast-changing world’?

by Douglas Worts

Jan 23, 2019

Traditional Investments and Stock Markets are a Powerful Manifestation of Our Culture of UNsustainability – And Museums can Intervene in Positive Ways

Toronto Stock Exchange, 1878, WikiCommons

Toronto Stock Exchange, 1878, WikiCommons

One of the most potent forces that drives climate change is the world of investments. Through the leverage of massive amounts of money accumulated in retirement funds, as well as in the bank accounts of corporations, plus wealthy and ordinary people, the traditional profit formulas of our ‘market-based economy’ have fuelled the proliferation of greenhouse gas emissions.

In recent decades, some governments have tried. with lacklustre success, to put in place policies and laws to limit environmental and social damage from business operations. Often these efforts are simply undone by other governments that are less willing to follow the insights of science and good sense.

Meanwhile, some businesses have been striving to reinvent themselves so that they are able to generate net positive value across social, environmental and economic domains. ‘Social enterprises’ and ‘B-Corps’ are examples.

Similarly, individuals and some businesses have embraced the world of ‘ethical investments’, using a series of screens to help focus on net-positive value generation, and to minimize negative environmental and social impacts.

In recent years, at least in some parts of the world, progressive stock markets have been requiring businesses that want to be listed on these exchanges to subscribe to ‘greening’ principles. This has often taken the form of measuring and managing carbon emissions, energy efficiency and social impacts. Now, the Toronto Stock Exchange is finally moving in this direction – albeit timidly. This article, in the National Observer, provides insight into this process.

The point here is that, as these changes take place, there is a need to support such efforts, and to foster greater public engagement and acceptance of the directions they represent. Of the myriad ways that museums can launch new types of climate-change-oriented public initiatives, this is one of them.

How our society has approached the generation of value is both quirky and now demonstrably lethal. Museums do have the ability to shine a light on the deep cultural values related to power and wealth that have driven traditional growth-based economic systems. And museums can also engage publics in discussing, imagining and generating a vision of the future, to which our broad communities can subscribe.

National Observer: article, The Toronto Stock Exchange is joining an international network that wants to green financial markets, Jan 17, 2019

August 29, 2018

Temperature Changes from Around the World, over the past 137 Years — Climate Change in Action

Yesterday, Canadian astronaut Col Chris Hatfield, posted the animation below. It is based on data derived from historic sources & NASA – National Aeronautics and Space Administration data, via https://anttilip.net/).

Generally, the Earth’s climate changes over a long period of time. However, in this era of ‘climate change’, the changes have been accelerated in dramatic ways. On a day-to-day basis, some people see a lot of beautiful days, mixed with some days of poor weather. These folks do not hear any alarm bells. One of the reasons for this is that the data – the feedback loops – seem like they are operating in slow motion. But when historical data, from reputable sources such as NASA, is compiled and provided in a way that condenses the trends into a short time frame, then even skeptical people will feel the impact of what is happening to our world. This short animation is an example of a compelling feedback loop on the increasing frequency of climate temperature extremes.

But it is not enough to simply demonstrate and teach that there are forces at play that need to be acknowledged, heeded and responded to. Humanity needs tangible ways for people to become personally involved in envisioning and creating a future that is both possible and sustainable. Embarking on such a path requires courage, humility and a willingness to examine the forces that are causing destructive trends in global, biospheric systems, like weather.

It is not possible to simply intervene in the weather systems themselves, because the causes are not to be found within the weather systems themselves. Rather they are to be found in the social, cultural and economic systems that shape human cultures around the world. Humanity has learned that climate change is caused by many things, but the biggest culprits are the loading of the atmosphere with Greenhouse Gas emissions (GHG) – much of which come from the creation and burning of fossil fuels as sources of energy. And the burning of fossil fuels is a central driver of local/global economies that have been designed to rely on: a linkage between money and power; an economic system that must continuously grow, or it is thought to be broken; continuously increasing consumption of goods and services; planned obsolescence (to keep people consuming more stuff); and more. Beyond this, GHG loading of the environment is associated with most forms of travel; most forms of heating buildings; and for generating a large portion of global electricity supply. This is why so much focus is often placed on the need for developing a renewable energy sector (which has just been dealt a damaging blow by the Ontario government).

So, as museums attempt to become change agents in the face of trends like ‘climate change’, they may first need to devise a multi-step approach. Such a plan would likely involve steps such as: engage the public in developing an understanding of what a changing climate looks like; helping populations everywhere to understanding how human activity and systems are actually destroying planetary systems; engaging individuals, groups, communities & organizations everywhere in co-creating a viable vision of a future that enables human and other life on Earth to flourish indefinitely; and, collaboratively generating steps to bring about the necessary changes to realize the vision.

There will be no quick fixes by new technologies, although new technologies will play important roles in realizing new visions. The hard work will be in re-building new cultural foundations that help to shape the transformation of many/most of the human systems with which we are familiar and relatively comfortable.

by Douglas Worts

April 23, 2018

For over two decades, my work has focused on understanding and discussing the intersection between the rather vague concept(s) that we call ‘culture’ and the burgeoning, poorly understood and often misused concept of human ‘sustainability’ on planet Earth. I recently re-read my first published article on the subject, which came out in 1998. Published by the Museés de la Civilization, located in Quebec City, Canada, for ICOM Canada, this little-known volume collected contributions from numerous museum specialists on the topic of culture, sustainability and museums. Although twenty years old, I feel that my little contribution remains relevant to the core cultural needs and opportunities that museums face today.

*****

(Originally published in Museums and Sustainable Communities: Canadian Perspectives, published by ICOM Canada, for the ICOM/AAM led conference ‘Summit of the Museums of the Americas’, Costa Rica, 1998)

“On Museums, Culture and Sustainable Development”

by Douglas Worts, Educator, Canadian Art Department, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Ontario

What good are museums? How do they contribute to society? What measures do we have for gauging their impact? Can their role be modified to better serve the cultural needs of an ever-more complex society? These and other related questions have nagged me for many years.

Increasingly, I am convinced that museums need a larger and more fully articulated framework in which to operate than that which currently exists. For the most part, museums see themselves in some kind of vague public service role – a role that is loosely thought to be fulfilled through the occasional visits of individuals. Frequently cited statistics indicate that a large portion of the North American population visits museums in any given year. If examined closely, the financial cost of these visits can be very high (from about $5.00 per visit to over $140.00 per visit). But in addition to the financial aspects of understanding the effectiveness and impact of museums, I would argue that the real cultural needs of our society cannot be met through the occasional nature of most museum visits. Culture is a process that is much better integrated into people’s lives than that. For the most part, the cultural life of Canada (and most other western nations for that matter) is more significantly reflected and directed by both popular culture (for example: television, media, etc.) and by the economic orientation/preoccupation of our society. Although unavoidable in our world, such strong private-sector influence over social/cultural dynamics creates a dangerously superficial situation that does not penetrate into the emotional, intellectual, imaginary and spiritual depths of human cultural needs. If museums want to play a more substantial role in promoting the healthiest cultural dynamics possible, particularly in the realms of facilitating symbolic experiences with significant objects or through creating relevant forums for debate and discussion about our histories and futures, then there needs to be some serious rethinking of the overall framework for museums. This should include the development of a set of performance indicators that reflect meaningfully on the qualitative, as well as quantitative, impacts of the museum.

Having been involved with the area of Sustainable Development (SD) for more than a year, I am inclined to think that SD might provide a conceptual reference point that could help to reframe the role and potential of museums. The term Sustainable Development has many unfortunate associations with a perspective that multi-national corporations are using to rationalize their continued growth. However, the notion of sustainability as a holistic world view that aims to meet the needs of the human population while maintaining the natural environment in an un-degraded form provides a potent vision for all individuals to work towards, regardless of one’s professional or personal situation. Applying this thinking to museums, one could imagine that the public dimension activities of these organizations could aim to create optimal means of fostering consciousness within society of the needs and impacts of human life on this planet, as they work towards meeting the cultural needs of individuals, communities, countries, humanity and the environment. In this context, the range of people-oriented needs includes physical, intellectual, emotional, social and spiritual. If adopted, such a vision would challenge museums to rethink many of their core assumptions, for example that exhibits should be their principal communication vehicle, and that collection-building should be a major preoccupation.

Through the LEAD-Canada (Leadership for Environment And Development) and LEAD-International programs, I have come to believe that a sustainable future for the world can only happen through a conscious participation in the issues that confront the global population. However, it is naive to think that people will gain a functional and responsible perspective on these issues until they have (at least) a good grounding in local/regional/national/ community dynamics. This is an immensely complex task, especially in the face of global economics, immigration, population trends, community fragmentation, pressurized work environments and rising poverty levels. If museums saw their main objectives in relationship to using symbolic and historic objects in facilitating healthy community dynamics relating to both archetypal and timely issues – at individual, community and global levels – then it may be possible for museums to reinvent themselves in a much more relevant form.

For this to take place, many things would have to happen in museums. First, there would have to be a reassessment of whether it is objects, or people, that are at the centre of the museum’s mission. Traditionally, museums have chosen objects to constitute their principal reference point – usually objects as understood from the perspective of one or more academic disciplines. Moving towards a more people-centred model would cause great chaos for many museums. Secondly, there would need to be a serious diversification of public communication modes within the public programming stream of most museums. Exhibitions, the traditional mainstay of public programming in museums, have the potential to be good at providing certain types of experiences, but are usually limited to the use of declarative statements about those viewpoints that authorities in a specialized field believe to be true. An increasing number of museums (although mostly in science and children’s museums – not in art or history museums) have already embraced the interactive, forum-based exhibit experience. For these organizations there is a commitment to engaging visitors in a knowledge-building process that negotiates rather than declares beliefs. But even at their best, exhibitions are generally not powerful or convenient enough to foster an integrated, ongoing and frequent-contact relationship between museum and the public, with the exception of a handful of museum enthusiasts. For museums to play a more integrated role, they need to re-evaluate the place of exhibits in their public programming activities. Although museums should never forsake exhibitions as a communication mode, there needs to be a serious expansion of alternative communication vehicles (such as community satellite programming, television, radio, internet, popular press, schools, etc.). Ideally, these modes need to be constructed within responsive communication links that allow for the flow of ideas, feelings and experiences both into and out of the museum. People need to feel that they are connected to the world they live in – that they are more than helpless receivers of information that someone decides is good for them. Such a change in direction is nothing less than a revolution for museums.

My work with SD has led me to believe that much of the focus to date in environmental biology, global economics, international law, inter-governmental agreements, and the like, will not lead humanity towards sustainability unless individuals at the grassroots level feel part of the process. And the process needs to honour a sense of the past (on individual and collective levels), the reality of the present (on individual and collective levels), and options for the future. In this sphere, museums can play a critical role – they have collections and insights that can provide access points into the experiences and wisdom of the past; objects that can help to focus on contemporary issues; and spaces that can bring people together to imagine and work towards an acceptable future. However, if museums continue to wander down the object-centred paths they have long been on, then the critical cultural roles relating to sustainability will likely be played, for better or worse, almost exclusively by the private sector (through mass media and commercial interests – who will be players regardless) and governments. But museums do have a chance to play a more central role in negotiating and facilitating our collective futures than they have in the past.

The challenge for museums is greater than a shift in philosophical position and vision – it will also require new competencies. As a 1997 report of the Human Resources Task Force of the Canadian Museum Association has made clear, there are many core competencies that are needed to operate a cultural organization. It is my opinion that many of these core competencies, such as those related to ‘vision’, ‘valuing diversity’ and ‘managing change’, are currently absent within the museum world. Additionally, knowledge of the dynamics of symbolic experience, identity building, assessing/understanding community needs, developing vibrant communication linkages to people and creating relevant focal points and forums for idea exchange are all functions that museums have very little experience with and competencies in – yet seem critical if museums are to be meaningfully engaged in contemporary life.

If the museum field decides that it wants to secure a relevant role for itself into the 21st century by embracing a central vision of Sustainable Development, then it will have a lot of work to undergo many changes in its practices and its performance indicators, as well as develop new professional competencies. The challenge is formidable, but the opportunities and the needs are immense.

by Douglas Worts

April 19, 2018

The True Costs of Collecting – Museums, Climate, and Carbon

This post was co-written by Douglas Worts and Erin Richardson. Erin is currently pursuing doctoral research focusing on the cost of collecting in U.S. museums. The piece first appeared in the Coalition of Museums for Climate Justice blog, January 31, 2018.

How much energy is required to maintain temperature and humidity levels inside a museum?

Because of the wide-ranging realities of museum environments, it is likely that no such aggregation of data has taken place. However, many individual museums have begun to ask penetrating questions about the carbon intensity of their operations. The links between environmental controls, energy and carbon emissions are both real and strong.

A major component of the carbon intensity of museums is related to storage, care, and use of collections (which applies 24 hours a day, 365 days a year).

In recent years, some of our colleagues, like Coalition member Sarah Sutton, have been encouraging and supporting museums in the development of responsible operations and actions that reduce carbon intensity. Collections care is seen by museums as central to their missions, while being a source of carbon emissions.

Collection-related activity therefore requires a close review of the assumptions underpinning this traditional museum function, including meeting optimal environmental standards, the necessity of objects in the museum, and the need to continuously expand.

Environmental Standards

Fine art and object conservators have recommended optimal environmental standards to preserve materials as long as possible.

At least for institutions in the West, these standards call for a stable environment of 70 degrees (f) +/- 2 and 50% relative humidity (RH) +/-5%. Such standards demand considerable energy to operate HVAC systems in areas where collections are kept, including storage facilities, galleries and special exhibition halls, as well as whenever in transit.

A large percentage of museums operate at these strict levels of environmental stability – believing that it is their professional duty to ensure that sector-wide standards are met.

Since a borrowing museum’s gallery and storage climate readings are always considered by the lender when approving a loan, many museums feel that without adherence to sector-wide climate standards, loans will be routinely denied.

There are museums, however, that do not adhere strictly to these standards – either because their collections are very robust and are not as sensitive to climatic shifts as materials made with paper, textiles, and organic materials; or, because they simply can’t afford to retrofit their buildings (often historic structures) with energy-efficient systems.

The Necessity of Objects

Traditionally, collections are seen as fundamental to museums – both by museum professionals and the public. It is true that material culture can be a powerful way to nurture the ‘muses’, thereby enabling citizens to feel connected to the past in ways that are relevant for both the present and future. However, objects don’t always have this effect, thereby raising the question of how public value is measured in museums and whether the exhibition of objects is the best way to generate public cultural value.

Most people will agree that museums hold a ‘public trust’. However, it is no small feat to define exactly what the nature of that public trust is, as museums strive to protect the material history of our pasts, while ensuring relevance to present communities.

There is an assumption, at least within museums that are supported by public funding, that the work of museums must contribute to the public good, which, like ‘public trust’, is also a vague notion. By fostering the ‘muses’ of creativity, insight, and innovation within the public sphere, museums and their communities have the potential for constant self-reinvention, so that they operate in timely and relevant ways amidst constantly changing cultural realities.